Jamie O’Hara Laurens

Jamie O’Hara Laurens

Websites: jamieoharalaurens.com

facebook.com/ppongfreepress/

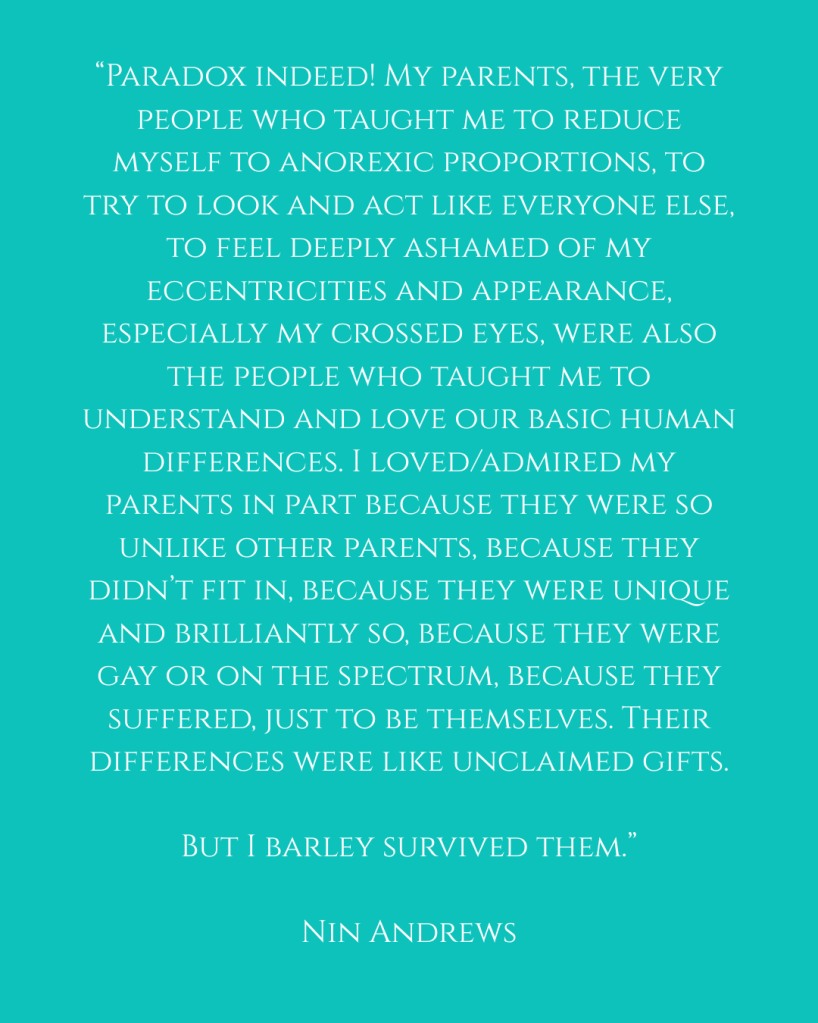

How do you wear your otherness? Is it comfortable? Are you a visitor to this space or is it as if you are sitting on the corner of a small soi as the traffic warms your seat on the edge of a marble bench? Are you at a dunken donuts while the wind presses and stares cherry lined blossoms into the sidewalk? Are you climbing the slip of algae licking the rocks of an ocean running into street art tattoos caves music your sexuality your age your home? Does your otherness melt away or build your sense of self? Is this empowerment or shame?

In her book Medaeum, now out from Ping Pong Free Press, poet Jamie O’Hara Laurens takes on the tricky character of Medea. “When you ask ‘Who was Medea?’ the immediate answer is that she committed the most unthinkable crime. My intention is to investigate with empathy her peculiarity and rage.” O’Hara Laurens confronts issues of feminism, otherness, domesticity, borderlessness, and language. The book is dedicated to The witches who must, which Laurens intimates, “allows for the uncomfortable notion that Medea is incarnate today in women who, caught between duty and true nature, are faced with impossible choices.”

Jamie O’Hara Laurens has collaborated with choreographers, sculptors, and translators. She completed her MFA in poetry and translation in 2014. A native to the West, she has an ongoing curiosity about the natural world. Recent work can be found in One, Enclave, The FEM, Alexandria Quarterly, and Hawkmoth. Medaeum was released in the fall of 2016 from the Press of the Henry Miller Library. She became a feminist writer by necessity. She lives in Brooklyn.

.

- If you were asked to create a flexible label of yourself as a writer, what would it be?

I might be a lyrical feminist who dabbles in time travel.

- In the first poem, “MEDEA RAISES THE WHITE FLAG”, we begin with, “The Proper Guide to Household Life / has fallen open on the counter.” As we read further we learn, “Wait: the blood is still in the bodies / & her pinafore is still tied. / The setting sun red-orange & tremendous.” Medea has not yet murdered anyone. She is numb with rage. In the next poem however “SELF PORTRAIT IN HER FATHER’S ORCHARD” we jump to a flashback of her previous young self, “lost in the blossoms’ fragrance.” It is here we are able to access issues of historical patriarchy and violence. Could you please introduce Medea, and describe why you chose her as a persona to straddle these issues on a more personal intimate level?

When you ask anyone “who was Medea?” the immediate answer is that she committed the ultimate crime, which is against the very things we hold dear. If she is a victim, it is of hysteria; otherwise, she is just a monster, and this makes it impossible for us to see her any other way. But she was also an immigrant, a warrior, and the gatekeeper who helped Jason win his famed and celebrated conquest. She inherited a talent for sorcery from her aunt, and was one-quarter divine. Medea fell in love under a spell, and became Jason’s right-hand woman, helping him defeat an army, get past a dragon, kill a king, and escape her own family. She burned bridges and committed crimes against her own family in the name of his pursuits. When they arrived back in his homeland, they had two sons, and then he left her for the young local princess to improve his social status.

I wanted to ask two questions: First, what if her crimes were metaphorical? And second, if we put them aside, what do we see when we make a fair study of her rage? Her crimes were crimes of passion, and crimes of passion come not from calculation but from reactivity to provocation. What I found was a woman afflicted with landlessness, cut off from her family, a woman whose strengths were exploited, who fought her partner’s battles, used her skills, and then was discarded. If we reimagine the murders as a metaphor for vengeance, or interpret the removal of her children in a modern context, such as a more mild rejection of family roles, or as a controversial abortion, a different, suddenly a modern narrative emerges: one that looks a little more like The Real Housewives, and a little less like Sleep No More. It was in my classroom that we came to the conclusion that if she has one single label, we are more at ease with her. But she doesn’t. She is ingénue, warrior, witch, herbalist, healer, battle axe, voyager, immigrant, wife, mother, and woman scorned before she is a murderess. We ignore her complexity and stick with the most comfortable name, so we can cast her aside and get her crimes away from us, like we do with anything we attribute monstrous qualities to. It keeps us safe.

- Medaeum in this uprooted or perhaps contradictory visible social structure is able to step outside of her social contract. In the poem, “DIVINER I (FIELD)”, “There were innumerable cells / to begin from. / Forty thousand thumb- / prints on the body / where one could strike up / a symphony of trouble / & call it love.” Medauem then questions her humanity in “TILL AND TROUBLE” asking, “What separates our sleep / from the sleep of wolves? // What separates our work / from the work of vultures? // Why, love why, do you look cornered? // Wind, we are sick. We are sick and beautiful.” Medea in her transformative process becomes closer to the natural world. Could you intimate why you chose to bring her closer to the position of medium? How is this reflected in her remorse?

Medea spends the better part of the play tortured by what she perceives to be inescapable and inevitable consequences. We don’t often carry this part of the play in the collective consciousness – that she laments what she sees as the only way to save her children from shunning and exile and an eventual fate similar to other children who had to flee across the ocean. Medaeum spends the better part of the collection reflecting on how she got where she is, deciding not to have twin sons, and contemplating the murders she doesn’t actually commit, except of her own self-concept, which she escapes by distancing herself from the social construct and as a survival mechanism, aligning herself with her own animal nature and the natural elements in her foreign surroundings. At the turning point, where she is rejected and begins to retreat, she is more of a Mary Webster from Margaret Atwood’s “Half-Hanged Mary,” or a Hester Prynne—a woman who knows more than she should, who knows also that she has been shunned. She is already more in touch with the natural world as a sorceress, and turns to that aspect of herself in refuge, but for the strength to do what she foresees as inevitable—ending the potential future of her offspring (in this case, ending pregnancy). Like the women in witch stories, being shunned, rejected, or convicted lead her to contemplate criminality.

- The degradation of reality shifts to the disintegration of language structure. In “BOXING THE COMPASS” she struggles with, “testing / my new language, / holding the old one inside / my tongue’s folded flag, / a closed tattoo / in a fold of skin. // When I opened my mouth / Atlas & witchbody moths / flew the coop.” How do her issues of displacement give resonance to and invert her shame on the level of language?

Some believe that place and person are inextricably linked, that landlessness leads to a sort of unhinging, an inevitable loss of some part of the self. The experience of immigration is different for everyone, but for me there were many moments when I felt like I could wear my otherness like a skin, when I was considered to be an aberration, a shame. The spoken accent is something we can try to abolish, but when we do, we erase a part of ourselves. Medea gets in trouble for being different, and for speaking up against authority, for not being able to keep her barbarian outsider mouth shut. At this point in my re-imagining of the story she is going through the erasure of the self that comes with trying to fit in, failing, and trying again. She also experiences an inability to find an outlet, to put words to her experience. In a few texts about similar experiences, we could perhaps call them witch narratives, shame starts outside the self and mores inward, from the external world to the internal.

- Medæum slips further and further from her definition of self. The regression seems to suggest an ancestral mindset which displaces us into similar issues that occur regularly in present society every day. In “NOT QUITE A MURDER” she states, “My ancestors divined it: / I hate to be the bearer of bad news … I drive a knife into the earth / just far enough to scare up a shudder— // not quite a murder / of crows.” Can you iterate how closely this reflects contemporary issues in the news? Was this intentional?

Medeaum cannot fit in the confines of the domestic arrangement as it is imposed upon her. At this point in the narrative she senses the threat of breaking with it within herself. I see this drama playing itself out over and over again in contemporary culture, in narratives of possession, in the coding of social contracts, and in the stretching or acceptance of that coding. I see her moving away from traditional structure as she grapples with the conundrum of her true nature.

The next—or rather, the very current and necessary— frontier of feminism, is deeply domestic. Couples in gender-normative roles will need to find the way to dismantle the expectations they set for themselves. Those who have embraced queerness and otherness by necessity perhaps will become role models for reconstructing them.

- We are offered a scenario consisting of a bird and a house. The bird is free outside of the house, but a nuisance inside of the house. Medea likewise is both inside and outside of the house simultaneously twisted in multiple spheres by her social contract. At the end of “DIVINER III (ANOINTING)”, we hear her say, “What whispers in my ear? // Dear Everyone, / Please, let me / let me disappoint you.” Considering this, could you please expand on the two lines in “& REQUESTS SEPARATION”: He says: you’re not a bit tamed. / She says: I’m untranslatable.”

Yes, the bird as a nuisance, or a prescient haunting in the house, was intended to show the discomfort of knowing what we don’t want to know before we know it, or before it has been confirmed. It was inspired by true events. It indeed does resonate with her dilemma and acts as a metaphor for her discomfort. A metaphor about freedom and entrapment could be found in the image of a bird in the house, but it is traditionally viewed as an omen, which was my intention. She has a failure of memory as she tries to remember the expression “a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush.” Is this because she has lost touch with her native language? Or because she is so unable to reconcile with her current situation that she can’t quite locate the folk logic on whether to go, to stay, to keep the pregnancy? I’m not sure. I’d rather let the reader decide.

At the end of “Diviner III” she grapples with the notion of the expectations placed on her as woman, wife mother, in opposition with what she describes to be her true nature—soldier, and the facet she takes refuge in— the sorceress. The only way out of the trap she is in may be failure to perform the role of indulgent wife and mother. She says in her famous address to the women of Corinth that she’d rather be on the battlefield than in childbirth.

The lines from “& Requests Separation” suggest that the failure of the union is blamed on the woman being too wild, untamable, while Medaeum knows that Jason cannot grasp her complexity. We can see in Jason’s language for and about her that she is at fault for being an inconvenience to him—too strong, too wild, too different.

- I would like for you to touch on is Medea’s continual reference to a captainless ship. She relates these to failure and solitude. In the poem, “MEDEA COUNTS TO ELEVEN” she says, “I woke up one day on the wrong end of a country song. // Flung from loveless authority. // Holy Fuck, I thought: This is the captainless ship// This is the captainless ship //Screw the captain shit.” And at the end of the poem we are told that she grows fangs and states: “I empathize with vivid garçons. / I run my tongue.”

As the captain of the Argos, Jason left his boat of heroes to settle with Medea; and subsequently abandons the ship of their marriage and family. The captainless ship refers to the vessel of the Argos, and to the household without the presumed driver, who has abandoned his traditional role, leaving Medea with the two children to fend for themselves. Medaeum is at once bewildered and enraged that there ever needed to be a captain, and that the captain who insisted on his role has left. What to do with the Argos when the captain has fled? Careful reading of Jason’s personal life such as it is possible, given that it is mythology reveals Jason to be more ringleader than hero. The animal grows in her beyond Medeaum’s will. Euripides painted Medea as a victim of passion: “passion is a curse.” She was in trouble with Jason prior to his departure to move in with Glauce (Medea’s Becky) because she spoke frankly about the political leaders of her time. So when she “runs her tongue,” it is both colloquial and literal—she runs her tongue with the need to speak too freely or too often, and runs her tongue over the fangs of her anger, her newfound animal nature.

- Lastly, in “CONSIDER THE GHOSTED LIVING” she is neither living nor dead. She states: “Do not ask me, ever, / who I do and do not forgive— / least of all, myself.” Could you comment on her struggle to find faith in any structure as she finally intimates in the last stanza of the book: “Is that what I was? A misbehavior? / See, I have outgrown the signifier, / have outgrown being the signified. / O! To have faith in something new.” And how does this relate to the very dedication in the forward, “For the witches who must”?

Medeaum’s only faith resides in the reinvention of structure outside the norms. This modern interpretation of the character has chosen to end a pregnancy, to divest them of their swords before they have them, and must leave as a marginalized Other; a process she is reluctant to undergo even if it suits her better. A woman who has carried a pregnancy carries the DNA of that being in her blood until her death, and so it can be a very difficult process to reconcile with. Medea may be considered sociopathic. I wanted to present a version of her who wasn’t. Medeaum hasn’t and cannot and won’t absolve herself entirely, but she will forgive herself enough to be able to survive. So she abandons being the “sight,” being the “signified,” being a woman possessed in a traditional role, and leaves in pursuit of ‘something new;’ a future time, or a future self, where there will be room for her.

Medea’s departure at the end of the play is considered widely to be a miscarriage of justice— an unmerited deus ex machina. Why would a monster get to ascend to the sky and escape? I tried to make her modern counterpart face an unchartered territory in which she would have to reassemble her relationship with the world.

It does mimic somewhat my own journey through process I both needed and feared. Nobody died, but my own image of what I and family were supposed to be had to be “cut from with a violence.”

I am weary of the endless feminine apology. It goes without saying that I protect my child’s life with my own; that this is what they need and deserve. Where I find an affection of a sort for a monster like Medea is that when you look beyond the unthinkable and try to really see her, you see the trappings of feminine power that have threatened over the centuries in a single character: the cauldron and the sword, the seducer and the banshee, the power to take away life as well as to make it. We can’t handle her. But on a metaphorical level beyond any crimes, I believe that may be a good thing.

- What were the first inspirations that made you desire to become a writer? Who are your favorite writers and how did they change over time?

I love harmony, language has the power of casting a spell, and voices that seems to reach through time. I’ve had an obsession with borderlessness. Among the first “aha” moments I remember were reading and rereading Hurston, hearing TS Eliot’s voice, and watching Brecht performed live, seeing Robert Wilson’s plays, reading about Rothko, watching PJ Harvey and Bjork; reading Marquez, Blake, Chekhov, Kundera, Neruda. My favorite writers are the ones who acknowledge, see through, and play with music, time and space– like Keats’s living hand that reaches toward the reader.

The desire to become a writer is troublesome. Like many things, we mistake the verb for a noun. I come from a family with a musical ear, but hear words instead of music, and I just have always wanted to write. In my dreamscape, I hear things, and especially in the place on the edge of sleep .

- Who have been the creative inspiration / mentor writers in your career?

There are the writers I turn to for technique (Hopkins, Berryman, Ashbury, Hirschfield, Niedecker, Levis, Graham, Carol Frost, Brigit Pegeen Kelly) others I turn to for inspiration, solidarity and companionship, like Caroline Bergvall, Alice Notley, and Ann Carson. I enjoy the poetry that is in conversation with other genres, like the fertile modernist period.. I definitely feel the importance of a feminine aesthetic lineage. Carol Frost taught me to put my heart back again and again to the work, and Malena Morling taught me to trust it, and to keep out of its way. Jorie Graham and Helen Vendler have influenced transformed my view of many things.

- How has your own work changed over time and why?

I’ve learned to completely separate generation and craft. They are two distinct practices. Generative work is like divination, and craft can be like automotive mechanics. I try to write what I’m told; as HD said, ‘follow my daemon,’ and then let it marinate for weeks before I return to it with the Allen wrenches.

- Have you been influenced by different genres, and if so how?

Yes! When it’s going well, writing is like quilting. Starting points sparks can come from random places; sometimes philosophy, sometimes a dog bark, line, to find a place to start, like striking a tuning fork. For Medaeum the play made the voice click into place. I’m afraid of being a poet who writes only for poets.

The most inspiring work I’ve read recently has been challenging, transgressing, and hybridizing genres. Ann Carson has been doing this her whole career, but more recently Ben Lerner, and Maggie Nelson, Sjøn, and Ta-Nehisi Coates are redefining the novel, the historical novel, and memoir in a way I find exciting—making story inhabit the body in a way it hasn’t before. We process information differently than we ever have. I’m curious to see what’s next.

- What are your plans for the future?

Right now I’m continuing to develop on Medea’s story in its larger context. I’m also developing a collection of urban-set eco-poetry inspired by the Symbolists. I want very much to make activism that matters without renouncing the privacy needed for creativity.

- What are your views on writing by women as it has occurred in the past twenty years?

I see a redefinition of boundaries in publishing which has led to a remarkable expansion in the number of homes available for a growing number of voices. It was not long ago that anyone who wasn’t male needed a man’s permission to be published. Now you can now find the words hegemony and patriarchy on advertisements in the subway. We’ve reached a sort of critical mass. The pursuit of agency has gone from being a radical choice, to a necessity, to a norm. We can work to join together excellence and truth. In the new cacophony of user-generated content, writing can feel like a competition to be heard, but we mustn’t fall into this notion. I believe we must turn to each other in solidarity and gratitude; in inspiration rather than in competition, because in fact the work may never be over. Right now, in the public sector, we are lucky to see a genuine shift, but the private life of many remains very coded. Alice Notley reinvented the epic with The Descent of Alette. Caroline Bergvall has been taking on language and the history of art and religion through conceptual poetry. Ann Carson has rewritten our relationship with classic voices from Sophocles to the Brontë sisters to philosopher Simone Weil. And now feminist writers like Claudia Rankine, Marwa Helal and Salwar Sharif are holding new mirrors up to nature and really rearranging the gaze. I think it is an incredible time to be a woman writer. We have taken the surface apart. Now we need to continue to go deeper, to find the next layers.

Jamie O’Hara Laurens

Jamie O’Hara Laurens