Category Archives: Annmarie O’Connell

profiles in poetics: Annmarie O’Connell

Annmarie O’Connell

Websites:

How do we write about love without being caught in a stagnant displaced and generic gestation? How does technology enable or deter our efforts to find true connection? Is this a manifestation of our commonality? At times we feel alone, we find intimacy, and we are utterly surprised by the individuals that reach out to us in the times we least expect it. We are at once unaided and enveloped, desiring deeply to find light in a world with much dark. Annmarie O’Connell is a poet who is witness to these moments of access and personal connection.

In her book, Her Last Cup of Light, out from Aldrich Press, we delve into the intrinsic aspiring desire to honor poetry, “for new love”. There is redemption here, one she describes as “a fighting chance”. The moments we share our true selves with others include those willing to share their “last cup of light”. “Beauties,” she says in a world that demands this necessity. In this place we never want to wait to leave, a moment between that breathes, that poem, for new love.

Annmarie O’Connell is a lifelong resident of the South Side of Chicago. Her work has appeared in Slipstream, Whiskey Island Magazine, and several other journals. Her first chapbook, Her Last Cup of Light, was published this summer by Aldrich Press. And she also adores you. I swear.

.

.

1.) What were the first inspirations that made you desire to become a writer? Who are your favorite writers and how did they change over time?

I started writing what I considered poetry at a really young age. I remember my first poem I ever wrote was in 5th grade about Jesus wiping the face of Veronica and how beautiful I thought she was. I didn’t really stop writing ever since. I think a lot of that had to do with my siblings. I come from a big family and they often encouraged me to do anything that would keep me out of trouble. And my teachers. I had a lot of pretty great English teachers. I went to a community college on the South Side of Chicago and studied with Eugene Bender who had earned an MFA from the University of Iowa. He introduced me to Sexton and I read her obsessively. He was so convinced I had a story to tell. I think I grew away from that confessional kind of writing as I started telling it. I then moved on to reading a lot of the New York School poets. There was a freedom in them that I really needed in order to write in a non-restrictive way. So Ginsberg and Koch were a dream to me. Now I love reading Malena Morling, Adelia Prado and Roberto Bolano. There is a sense of meditative silence in their work. And compassion. I want to be right there with them for all of eternity.

2.) Who have been the creative inspiration / mentor writers in your career?

I feel I have had this tremendous blessing in my life to have such incredible mentors at New England College. Jeff Friedman has always been an incredible source of creative inspiration and support for me. He has the ability to get you obsessive about your own work and to actually feel like the work itself deserves it. He gets me moving. I also worked with Paula McLain and she is like a God send to me. She gets it. She just gets what I write and makes me feel like it is necessary. Like the world needs it. You can’t ask for anything better than that. I’ve also worked with Malena Morling and her poetry has really inspired me to write and view the world in a different way. In an almost elevated way. As poets I think we do that—navigate the world on a different plane. I love it. I live for it. Her poetry gives me permission to.

3.) How has your own work changed over time and why?

My work has gone from this really sort of inner place that wasn’t really saying what I really wanted to say in the way I felt it working on the inside. Or maybe it just wasn’t quite there. Maybe I wasn’t all there. I think my work has changed as I have changed. I think there needed to be a moment of acceptance for me in order to get to the next place in my writing. Acceptance of this lifestyle. Because I really think being a poet is a lifestyle. And it’s now everything to me. Once I did that, I was able to get outside of myself and pull from the world around me in a really balanced way. In a really compassionate way. I want my poems to speak truthfully to how I genuinely feel and live. Almost in a spiritual sense. Which, now that I’m saying that, is sort of how it all started for me. With Veronica and Jesus’ face. I think we have to save each other. The world is beautiful and terrifying but I love you all anyway and fearlessly. Here’s my poetry.

4.) Have you been influenced by different genres, and if so how?

I really just focus on reading and writing poetry. Lately I have been reading some prose and creative non-fiction. I am amazed by the skill. I like to keep my eyes open and pull from all of that—especially the way it ties up all the loose ends so quickly. What it does in that tiny space. It blows me away.

5.) What are your plans for the future?

I recently published a chapbook, Her Last Cup of Light, with Aldrich Press. Now I’m working on writing and submitting a full length manuscript to several places. Aside from wanting to publish more poetry, I want to continue to adapt and grow and move forward with this lifestyle. I think that’s a huge part of it, too. Maintaining that sense of who you are. And as women I think we struggle with identity at times. We’re friend, mother, wife, sister, etc. We have so many roles we are expected to play. But we are also poets and writers. And our environment should be one that creates a space for that and fosters it. I guess I just want to make sure I am living my poet life to the fullest. If I’m not, then who will do it for me?

6.) What are your views on writing by women as it has occurred in the past twenty years?

I want more! I want women writer’s to be at the top of my sons reading list when they get into school. I want that future.

7.) Who are promising women writers to look at in the future?

I would definitely say Lauren Gordon, Joanna Penn Cooper, Sara Lefsyk, Anchia Kinard, Mary-Catherine Jones, Nikoletta Nousiopoulos. I know of many more but I am (so luckily) pretty much continuously exposed to their work. And it’s just brilliant. Each woman has a unique language that shapes the poem into something that is so exclusively them. And they’re beautiful.

8.) If you were asked to create a flexible label of yourself as a writer, what would it be?

I’m a South Side girl living in a heartbreakingly gorgeous world.

9.) In your chapbook Her Last Cup of Light, “the first afternoon after the day” we humidly coalesce a fleeting moment. Too easy to sweep by, we read, “You will get on the bus and tell the mother / who wipes the corners of her baby’s mouth / something about the hardest part / of beginning again”. After vast ruin it is both difficult and expounding beautiful to live in the world and find hope. Unwound further, “I will be the passing shadow / across your knees / loving you.” Who is the “you” in this poem and is that critical to how we interpret the piece?

As I was writing it, I really had this back and forth range of crazy emotions about my son, my unborn son, and their father. I think I really pictured it being all of them in a way. I think we all have moments in our lives where we deeply question our place in the world. And we fall so in love that we don’t ever want to leave, especially by way of inevitable death. I think that’s what new love is—that breathless moment. I think we’ve all had that to a degree. I wanted to write a poem for new love.

10.) The hope in the poem “When you lean your head on my back” here is thick, and so is the loss. We read, “I remember how you stepped / into the world early, / shouting / it is not lonely / dragging us off our knees.” Is this a conversation with redemption, and if so, where does the loneliness stop? Is loneliness learned absence, can redemption only live in childhood, or in the dirt? To further this thought, do you suppose that loneliness is a culturally inferred construct promoted by the tools that we use to connect?

Technology enables us to connect on the surface to many people, but does this draw us away from what we most desire; the redemption able to pull us out of the position we define cradling our knees? I think it definitely is a conversation with redemption. But maybe only a fleeting redemption that is fluid in a way. The loneliness I was referencing was the complete loneliness I think we all feel from time to time—like we are sort of beautifully lost in the world with no one to really get us and we really feel, simply put, alone. And you’re right, there’s a specific kind of redemption that is particular to having a child. It’s almost like a fighting chance. Technology is something that definitely hinders us from achieving any sort of truly, passionate, palpable existence. It’s the block in the road to togetherness. I am not made for the future.

11.) In “Compared to the sweet lilacs,” we are dead stars and still the speaker wonders “what stops you / from leaping into the arms / of the stuttering man on the street, / his body a distant shadow … I’m going to tell you to kiss his narrow mouth.” What stops us? In the poem, “The boy drags his doll,” the boy’s heart turns, “into whispers / for mile after mile.” How does he get his heart back and why was it left with the boy and the doll?

When I was writing “Compared to the sweet lilacs” I wanted to convey the fact that we are often terrified to do something as crazy as kiss the man on the side of the road. Or do anything we actually feel like doing right in the moment. I think we plan too much and shut down a spontaneous part inside of us that’s just so desperately the real us. People deserve the real us. I also wanted to convey that I think we should love him and talk to him and learn him and experience him. So what does stop us? Ourselves? Fear? Standing in line? I don’t really know. But I don’t want to ever stop loving. That’s what I know.

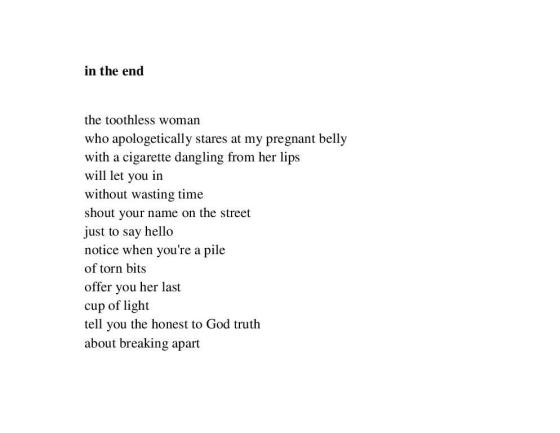

12.) The conversation shifts in the poem, “In the vacant lot”. We read of the speaker’s desire to heal ideological wounds split into the palms of a man. She says, “I want to smear love / into the grooves of his palm // sometimes you can see the light turn on in things that are alive.” And then she continues, “just to say hello / notice when you’re a pile / of torn bits / offer you her last / cup of light / tell you the honest to God truth / about breaking apart?” Why does she want to offer her last cup of light and where is his agency? Her message at the end of the book is, “you want to tell him / that at the exact moment of death, / we’re navigating / in the weeds,” where is his light?

All of the people in the poems are people I actually encountered walking around the South Side with my son in our neighborhood. The man on the bus stop was so surprised that I spoke to him and offered him a hand onto the bus as he struggled so much. It was like watching something become alive in both of us. A validation to continue living and helping for me, a change in him maybe? It seemed that way. The woman I was describing, the one offering her last cup of light, is really a lot of the women you would meet here. Very loyal. Very willing to suffer for your happiness. Very honest. Very, very honest. Beauties really. In the last poem, I really wanted to wrap up the chapbook in a way that conveyed the fact that we are all grappling in horror and pain and shabbiness and things we can’t control, but we can still find the beautiful things. Look for the beautiful things. And love with all your might.