How clearly and explicitly interwoven is shame into the grit of trauma, erasure, and oppression? How does one honor the intensified humiliation of rape personally, publicly, and in shared spaces? How does society participate in the bondage? How does isolation from similar experience lead to shame and learned helplessness? Who must do the healing; their feet unbound? And how can community instead be a leading illumination of experience, the recognition of ignorance, and the witness of it?

Today is delightedly the exact 13th year anniversary of my first interview with Selah Saterstrom in ’12. And in the power of this transformational number and this second interview, we are encouraged to committedly sing into this lamenting space. We reflect on her novel, Rancher out from Burrow Press, ’21, where she confronts the ricocheting illumination of erasure, humiliation, and violence asking first of her own rape as a child: ‘what is an essay of rape supposed to do?’.

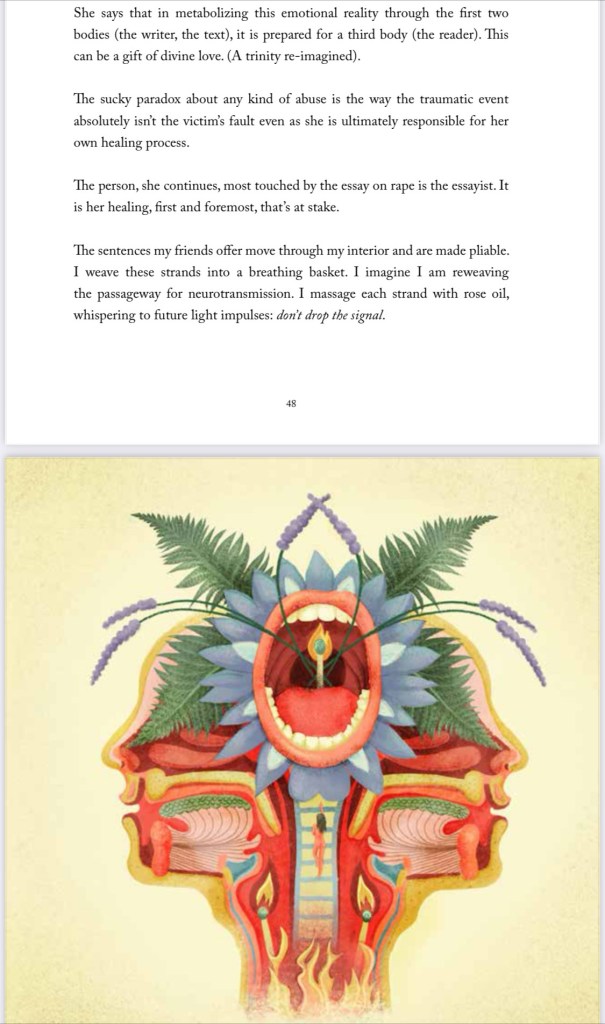

Selah’s essay-excerpts traverse back and forth, in form and interrogation; resisting the linearity of the essay form in dream, memoir, research, and reflection. As she describes, this ‘call and response’ jazz funeral embodiment, beholds the breakdown of ideals and exposes the uprising of the accountable. She expounds the necessity to bear witness and hold space to sexual violence and to unify the self between what we do and what we feel. This is a space that confronts illusions of mass shame, where survivors instead are visible and supported in affirming their truth and dismantling saturations of power and violence. As a writer who has recently moved to the striking beauty of the Vashon Islands with wife and daughter, she says she is ‘forever unfolding into new constellations of possibility’.

Selah Saterstrom is the author of the innovative novels Slab, The Meat and Spirit Plan, and The Pink Institution, as well as two nonfiction collections, Rancher and the award-winning Ideal Suggestions: Essays in Divinatory Poetics. She is the co-founder of Four Queens Divination, a platform dedicated to the intersection of divinatory arts and creative writing. With over twenty-five years of teaching experience in graduate programs and diverse settings worldwide, Selah now lives on Vashon Island with her wife and daughter. Long version HERE

– excerpt from Rancher

What were the first inspirations that made you desire to become a writer? How has your work changed over time and why?

Thirteen years ago—to the day—I first answered this question on your lovely questionnaire! Can you believe it? I can. #13 is my lucky number. I returned to my notebooks from that time and found myself caught in the architecture of an earlier self. What I couldn’t have known then was how profoundly life would reconfigure me—that both of my parents would soon die, that I would fall in love, marry, become a mother, that I would write three more books, that I would walk away from a Full Professorship to build a life where writing was not a pursuit woven around the edges of living, but its very center.

And yet, the original summons to writing remains unchanged—to cross the threshold where articulation meets erasure, to stake one’s life in language, that volatile, fugitive medium that both composes and exceeds the self. It is a continual reckoning with meaning’s emergence—unstable, recursive, forever unfolding into new constellations of possibility.

Your latest project, Rancher, addresses the question: What happens to the sexual assault victim? We read, “The sucky paradox about any kind of abuse is the way the traumatic event absolutely isn’t the victim’s fault even as she is ultimately responsible for her own healing process.” Can you comment on this?

When I set out to write an essay “about rape,” I put out a call to close friends and asked: What is an essay about rape supposed to do? The first quote you share comes from my friend Teresa Carmody’s response.

Call and response is one of the oldest structures—a rhythm of being met, a recognition that meaning is forged not only in words but in the space between them. It is an act shaped as much by listening as by speech, a testament to the necessity of witness. Growing up in the South, I first understood this through the Blues and the great lamentation-celebration of the Jazz funeral and second line traditions, where a voice calls out in grief and praise and is answered—not to solve, but to witness.

Witnessing is an act of defiance against erasure. Recognition affirms. Without it, suffering risks slipping into invisibility, and what is unseen is too easily dismissed. To witness is to engage, to take responsibility—to insist that no voice should exist in a vacuum. Healing requires resonance—pain left unrecognized remains closed, looping inward. But witnessing creates an opening, an echo of connection that reminds us suffering does not have to be a private exile but can be part of a shared human condition.

Enter: friendship. Trauma isolates, pulling a person out of the shared world. But the sacred call and response of friendship insists that even the hardest truths can be spoken, received, held. It affirms that healing, like harm, happens between us.

In Rancher, you also write, “another aspect of life after rape: the unforgiving public.” Can you unpack this sentiment?

The hero Gisèle Pelicot’s ordeal (at least 51 rapes) inspired rare solidarity, yet the very exceptionality of her acceptance illuminates a deeper, systemic mistrust of survivor’s truths. Even now, from the highest corridors of power—the White House itself—comes public support for formally accused rapists (Andrew Tate, Tristan Tate, Conor McGregor), a stark reminder that truth remains captive to those whose power depends on doubt.

Eric Aldrich’s review of Rancher meant a great deal to me in part because it articulated something fundamental about the structures that enable violence. He wrote:

“Saterstrom offers glimpses of…the community that harboured her rapist… As a person who grew up in a rural community, I recognized the types of dumbness and awfulness endemic to…the victims of sexual violence in my own hometown. Rancher clarified the connections between humiliation and sexual violence that I’d only sensed before.”

His review recognizes a world where insularity breeds impunity and where cruelty, left unchecked, becomes culture. Rancher was, in part, an attempt to make these forces legible.

Violence does not often arise in isolation, nor is it merely the sum of individual acts. Rather, it is embedded within a culture—normalized through its failures to intervene and its tacit permissions. Humiliation and sexual violence are not separate forces, they are interwoven, reinforcing each other in ways both insidious and overt. This is also very much about the mechanisms of shame that ensure suffering remains private, unseen, and unchallenged.

In 2023 – 2024 (according to RAINN), out of every 1,000 sexual assaults, approximately six of these resulted in the actual incarceration of the perpetrator. These numbers lay bare the staggering gap between the prevalence of sexual violence and accountability.

Communities uphold these injustices when they protect perpetrators over survivors and when accountability is framed as an individual burden rather than a collective responsibility.

The question, then, is not just how the community sustains this reality—but how it might dismantle it. And it is this question that I was interested in exploring in Rancher.

Who are promising women writers to look at in the future?

I may not be answering your lovely question directly, but if you’ll indulge me . . .

So many extraordinary writers working beyond the mode of the straight male author are shaping this moment—not as emerging voices (a term that often obscures how long they’ve been making essential work) but as forces sharpening our capacities for thought. My attention isn’t on career arcs—visibility is a strange currency, and what we call “new” is often only newly recognized by the machinery of big publishing.

Recently, I’ve been very excited by Chanté Reid’s Thot and Jade Lascelles’s Violence Beside. Gabrielle Civil’s work continues to be astonishing—Experiments in Joy should have a wider readership. Queer Southern writer Justin Wymer’s essay, Love in the Time of Hillbilly Elegy: On JD Vance’s Appalachian Grift, is incredible – it cuts through political erasures with razor-sharp knowing. And Chris Marmolejo’s Red Tarot—from a queer Indigenous and trans perspective—is one of the most significant contributions to divination studies in decades as far as I’m concerned.

What are your plans for the future?

I’m about to send my new novel, The Delirium of Negation, to my agent—it is a mystery set in the underworld that revolves around missing women. Alongside that, I’m wrapping up a collection of essays on queer rurality and writing, work that feels especially alive to me right now. And if fortune favors me (and I don’t disappear entirely into the labyrinth of my footnotes), my very long book on the theory of divination should see completion by 2026.

Recently, my family moved to a small rural island. Life is contemplative, the Salish Sea dramatic! In the days ahead: more writing and spending as much time as possible with the people I love and of course, resisting autocracy.

BNI