J. Hope Stein

Website: http://www.jhopestein.wordpress.com

J. Hope Stein is a poet that evokes the lyrical expression of her craft and human meditations through persona, pop culture, constraint, and our evaluative methods of communication. Music, Playboy, film, and technological intermediary of intimacy dance in a playground of invention and our perception of this space.

Stein describes herself more as, “a listener than a writer”. She articulates, “I am drawn to experiencing history as a citizen does – without hindsight. I get very little from text books and biography.” Persona, in Stein’s work permits her movement through the weighty abstractions of human experience; “some kind of urge for life”. It is here she extracts, “love is the great antelope we make of each other — to me that is a hopeful statement about love and our individual capacity for invention and reinvention.”

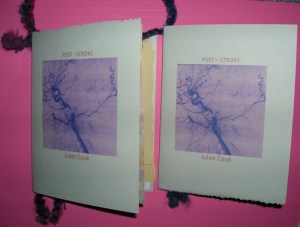

J. Hope Stein is the author of the chapbooks [Talking Doll]: (Dancing Girl Press), Corner Office (H_NGM_N BKS) and [Mary]: (Hyacinth Girl Press). Her full length manuscript The Inventor’s Last Breath was a finalist in the Alice James Books 2011 Kinereth Awards and her chapbook Light’s Golden Jubilee was a finalist in the 2011 Ahsahta Chapbook Contest. J. Hope Stein is also the author of poetry/humor site eecattings.com, editor of poetrycrush.com. Her short film, The Inventor’s Last Breath, based on her full-length manuscript about Thomas Edison, was screened at the 2011 Cinepoetry Festival at the Henry Miller Library in Big Sur and will be screened in several venues in 2012.

1.) What were the first inspirations that made you desire to become a writer? Who are your favorite writers and how did they change over time?

You’ve caught me at a good time to answer this question because I have been trying to figure out why I write the way I do and the answer I think is, that at the time I was learning to read (mostly children’s poetry: Robert Louis Stevenson, Shel Silverstein, Dr. Seuss kind of stuff) I was also sharing a bedroom with a woman who showed me tons of porn magazines–(long story). I would use tracing paper and colored pencils and trace pictures and words and put it together as a book and put my name on the cover. So, my writing has always been kind of a cross between Green Eggs & Ham and Playboy.

Over time I’ve taken in numerous influences– the best thing that I did in that regard is get an MFA at New England College which was kind of a boot camp in which I totally lost my ego– stopped thinking about what I liked and what I didn’t like — and just tried to read and absorb as much technique as I could.

2.) Who have been the creative inspiration / mentor writers in your career?

My mother was a music publisher so I was consuming lyrics at an intense rate. While I was growing up she represented the lyrics of everyone from U2 to Rodgers & Hammerstein to REM to Sheldon Harnick to Irving Berlin to Leiber & Stoller. And she would bring tons of music home and I would listen to and memorize all the lyrics.

My parents divorced when I was 2. So, growing up, I would see my father on Sundays and we would drive around and he had a new mix of songs to listen to each week and we would just cruise around and listen and that would be the emotional soundtrack of our day and I think that is how I learned to understand him. I mean, I was 5, 6, 7, and felt a very strong sense of communication with him without him saying too much about what was going on in his life. So, lyrics were very important to me at a young age. I could kind of know my father better by the choices he made and my mother’s business was lyric.

My MFA mentors from New England College were rather magical – as artists and as teachers: Ilya Kaminsky, Brian Henry, Malena Morling, Carol Frost.

I am inspired by many of my friends who are in all fields of art and work, especially my husband who is also a writer.

3.) How has your own work changed over time and why?

When I first started to try to write poetry it was when the person I loved most in the world died. I wrote a lot of short poems which were overwhelmed with grief and regret and guilt and self-loathing. One day I just woke up and took all my poems to the corner of 22nd Street and 7th Avenue and threw them in a garbage can and as a survival instinct I completely cut myself off from poetry and got myself a corporate job. It wasn’t until many years later— I fell in love again and got married, that I found myself writing again and it was at the insistence of my husband, who is also a writer, that I make writing a priority.

Around the same time I met Ilya Kaminsky at the Frost Place and read his book Dancing In Odessa on a train from Vermont to New York and by the time I was back in New York I was like– this is what I want to do. So I looked him up on the internet and emailed him and followed him to New England College.

When I started my first semester at New England College I was pretty determined to not write about the dead boyfriend. I think Ilya’s work helped me see how that is possible – his “we dance to keep from falling” attitude made an impression on me and the kind of writer I wanted to be. Also his love poems have this bringing-sexy-back to marriage spirit going on that is refreshing and I had just gotten married and it was a place I wanted to dwell in my own work.

To avoid the dead boyfriend I went to the New York Public Library and read archived newspapers. I think it was in his book Chronicles that Bob Dylan talks about when he first moved to New York City and started writing songs– he would go to the New York Public Library and read archived newspapers from the Civil War. He said that he did it because in writing his songs, he didn’t want to limit himself to his personal experience. So, rather than starting from a place of expression and emotion I was focused on research and technique and language. What resulted was a much more indirect dealing of my grief. One that inspired me rather than swallowed me.

I wrote a book length piece that was based on Thomas Edison’s last breath which was supposedly captured and saved in a test tube (on display in the Ford Museum in Michigan). So it was an exploration of that rather than personal loss. And I began to write longer narrative poems in voices of different characters. Focusing on technique and language and research and working in voices were all ways I think of protecting myself from what happened to me the first time I started writing poetry. So I was creating some distance from myself and I was learning a ton while doing it.

My second semester at New England College, I worked with Brian Henry and three really important things happened immediately in the first month which further changed my work. I read Brian’s book Quarantine, Notely’s The Descent of Alette and Inger Christensen’s It. They all have this incredible trance-y electric lyrical quality that mesmerized me. They are all experimental in nature and they all adhere to strict form.

The trance-y lyric made me realize what I wanted in the quality of my own lyric. The experimental nature made me more confident in my individuality as a writer. I began to trust my instincts. And with form – I finally understood form – not intellectually the way you are taught in school, but I understood it in my bones as a necessity for my poems to live. I really love Frost and I love to read his lectures, particularly his thoughts on form.

Currently, I am looking at all the material I have written over the past 3 years and there are lot of historical figures that I use — I kind of have my way with them to work out my own intellectual and emotional explorations. In that sense I’ve been a bit of a coward. Now I’m trying to pull a layer back and get a little closer to myself – not too close so that I will swallow myself up, but closer.

4.) Have you been influenced by different genres, and if so how?

There was a 1-person play I saw by Anna Deveare Smith called Let Me Down Easy that haunts me and informs my work. There is a final scene which powerfully describes the moment of death and I think that has been in my mind through much of the writing of The Inventor’s Last Breath.

CocoRosie’s first album which they recorded in a bathtub moved me by it’s sheer creative force and is part of what got me to start writing again.

Kanye West is big for me. When I first heard his 2010 album My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy, I felt like someone had just broken through to the new century. As though everything had been still and dead before that and he just broke through. I love his other work, but it’s that album that just woke me up.

The honesty of the Violent Femmes and Tracy Chapman is important to me.

The camerawork in Robert Altman films (especially McCabe & Mrs. Miller) as well as Peter Weir’s Picnic at Hanging Rock has a lot to with how I think in image. Sadly I can’t quite transform it into words, but that’s the goal.

The use of musical refrain– the trumpet—in Fellini’s La Strada. It’s a masterful and moving and meaningful use of repetition. Again, I don’t get there in my own work but that is the goal in my mind. That movie kills me in the best ways. And it has everything to do with that trumpet.

I am inspired by the creativity and the liberties of Todd Haynes in his loose biopics of Dylan and Davie Bowie. Most of my work is loose bio.

I just restructured my manuscript to follow the structure of Hannah and Her Sisters (although no one would realize it).

Archived newspaper. I read so much archived newspaper and incorporate it into my work. The research I did on my Edison manuscript was almost entirely based on archived newspaper. I am drawn to experiencing history as a citizen does – without hindsight. I get very little from text books and biography.

I saw an early cut of the movie Compliance last spring which I think is coming in theaters this year. It directly influenced one of my poems called Ted & Sylvia. Compliance is based on a true and very disturbing story of sexual crime. And there was something in that film that made something click for me and it continues to inspire my new work. Craig Zobel is one of my favorite new directors. He has a gift for nailing some of the honest and often ugliest aspects of the human condition.

I was away most of January in a remote place in the central mountains of Oregon, where I lived in a cabin and had a spurt of writing that I am grateful for. I was listening to this playlist of like a 100 tracks in constant rotation: Beirut’s new album, Lovers- past 2 albums, Olof Arnalds – all albums, King Creosote & Jon Hopkins new album, live readings from Hayden Carruth, live readings of John Ashbery, Live readings of Wallace Stevens, the new album from Little Scream, the new album from Active Child and James Blake’s latest album. The energy of these works, in my mind, is very connected to energy of what I wrote.

That’s just the first few things that come to mind.

5) What are your plans for the future?

I’m continuing my new work – Lob Story. I’m going to be a story editor on a film project. And have some other short film pieces I’m working on. I have a new chapbook in July called [Mary]: (Hyacinth Girl Press). I’m also collaborating on a project with Joanna Penn Cooper that I’m excited about. It is both artistic and philanthropic.

6) If you were asked to create a flexible label of yourself as a writer, what would it be?

I’m more of a listener than a writer.

7) In your chap book, Corner Office, published by H _ N G M _ N B KS 2012, we enter into a world of disassembled bodies that unravel and crumble into the passivity of tombstones. But while the body remains inactive, love is an action that breaks through the technological experience of our present everyday lives. You comment on this intimacy as it filters through emails, computer programs, office supplies, and windows. Seemingly searching for the warmth to utter, “I lob you”. Can you discuss how you see intimacy interacting in our present technologically focused culture?

Hey, it’s funny you should pick that line “I Lob You” because I’ve expanded on that and have just written a new 20page chunk of work called “Lob Story”. I have never really asked myself this question about technology, but now that you mention it I can see that it is all over my work.

I have a metaphor in there somewhere likening the skyscrapers as growing towards sunlight like coral reef…and I suppose I was thinking about how on the bottom of the seafloor where there’s no sunlight – there are still urges for life.

The experience this was loosely based on was when I was sharing an office cubicle with this guy and there was a lot of sexual tension between us. In that environment with people around us all the time– being able to hear what we say and see us– the urge seeped through in strange behavior– the details about how he took pictures of me from his desk and emailed them to me…he took a picture of a picture of my mother (and hung it over his desk), those are details that stuck with me of this kind of strange intimacy that we shared. There was also something withheld that stuck with me. And in moments like this I feel like one can feel oneself being governed by something that is not really them, some kind of urge for life.

Regarding your question about technology– There were times when we were sitting right next to each other in our cubicle and he would both call me on the office phone and instant message me on my computer at the same time. And on the phone he would be like “hey, how are you?” while simultaneously instant messaging me “fuck you fuck you fuck you”. Those were the days! Now our relationship is a completely normal friendship because we are not in that circumstance. The urges play against the structure of the circumstance. In much of my work I don’t start with language, like other poets do (although I spend a lot of time thinking about language). I start with rules and form and structure because my tendency is for all urge so when I give my urges a structure to live within, it ultimately helps me find the tension.

9) Punctuation plays a commanding role in your collection of poems, Insomniacs. Described as “units of personality,” by your Thomas Edison character in the opening piece, we are visually able to see the subversive quality of punctuation. We witness how it affects our experience of language in the musical field of language in addition to how it is arranged on the field of the page. In the poem, “The Boy,” he “hears the earth/ in a series of dashes and dots”. And in “INVENTOR LOSES HEARING AS MOTHER READS WHITMAN,” there is a passage made up entirely of punctuation “You say you can feel it in your stomach. / .-.. — .- ..-. / — -. / – …. . / –. .-. .- … … // .– .. – …. / — . loose the stop from your throat.” We are also given footers throughout the collection of poems. Can you describe your intention behind this confronting punctuation and how it is evaluated on a universal platform?

My manuscript was about an Inventor character (loosely based on Thomas Edison) and I was doing a ton of research and Edison proposed to his second wife Mina by tapping on her wrist in Morse code. It was kind of like their secret language.

The second thing that gave me the idea was that Ilya had me reading Paul Celan’s “Death Fugue” – the version translated by John Felstiner– and he noted to me that it was interesting how in Felstiner’s translation he chose to keep in some lines in German and the power of that. So that planted the seed for me to have something on the page that was not fully translated — something that was preserved within the experience that I was translating from Edison’s life.

The Morse code came out of an instinct to make the work more visually mysterious to myself. As though it’s inhabited by something that I don’t have full knowledge of. This is similar to my use, which you mention, of the over 90 interruptive endnotes in my long poem Conglomerate. Like the Morse code, the endnote markings within the text represent something that is present but you cannot see it exactly. In that sense, there is something spiritual to me. And I agree about your observation of punctuation being musical. To me it’s very percussive.

I do think there is a connection between the “units” of punctuation and the quote I use from Thomas Edison regarding his theory of life and death and man being comprised of “life units.” I can’t articulate what, but I think you are right.

Regarding your question about punctuation on a universal platform. Punctuation, generally works as a breath manager – determining when you get to breathe. The book is called Inventor’s Last Breath and The Inventor has “breath experts,” so yea, I think that is all related.

10) Talking Doll, a chapbook from Dancing Girl Press 2012, focuses on the “Inventor”. The inventor orchestrates artists that “pencil 60 straight-edge diagrams,” “breath experts,” that “mold 30 different breeds of diaphragm,” “experiments of the flesh”. Love later we find out turns out to be an antelope head hanging over the mantle of a winter fireplace. As readers, we are confronted with the question: “is this love or experiment?” and when the response is love, “is it love for love or for the sake of experiment?” How do you see love functioning in these two separate roles and how does the role of the inventor or artist participate in this discussion?

To me, the inventor and artist are the same. Edison said you need to be a poet to be an inventor. I guess I see love the same way. You need to be a poet and an inventor. Certain people bring out different things in you, so there is the chemical/scientific aspect. Love has a lot of possibilities for experimentation and invention. The antelope over the fireplace image, just as I’m thinking of it now, reminds me of Woody Allen’s dead shark analogy from Annie Hall – in which he says that a relationship is like a shark and needs to move forward and if it doesn’t it’s a dead shark. But later I say something like — love is the great antelope we make of each other — to me that is a hopeful statement about love and our individual capacity for invention and reinvention.

The “Is this love or experiment” line probably is asking the question of whether something is purely chemistry or if there is something deeper. In the case of the Talking Doll (one of Edison’s inventions) – who is speaking in this poem as she is being put together by the Inventor — I think she is wondering if his motive is just to make her for the sake of a scientific invention – for his love of science — or if he is truly passionate about her. There was a crop of talking dolls that were defective — Christmas, 1889 or so — that were just piled up in Edison’s factory in a corner somewhere. One second they were the hottest Christmas item, the next, they were all returned to the factory because they didn’t work. Poor girls, I felt bad for them.